Introduction

Mastitis is the most common disease of dairy cows and the most common reason that cows are treated with antibiotics (Pol and Ruegg, 2007; Saini et al., 2012). Mastitis is a bacterial infection of the udder which causes inflammation (host defenses responding to the infection). Clinical mastitis occurs when the inflammatory response is strong enough to cause visible changes in the milk (clots, flakes), the udder (swelling), or the cow (off feed or fever). Most clinical mastitis cases are mild and cannot be detected unless foremilk is examined; a study in over 50 Wisconsin dairy farms found that 50% of the cases only had abnormal milk, 35% of the cases had abnormal milk and swelling of the quarter, and only 15% of the cases had systemic symptoms (Oliveira et al., 2013). Treatments of mild and moderate mastitis are not medical emergencies, and treatment protocols should allow time to review the history of the cow to determine whether antibiotic treatment is necessary. To ensure that milk is free of residues, producers, farm workers, and veterinarians must work together to design and use appropriate treatment protocols. This article reviews when and how to use antibiotics safely and responsibly to treat clinical mastitis on dairy farms.

Please check this link first if you are interested in organic or specialty dairy production.

What Types of Bacteria Cause Clinical Mastitis?

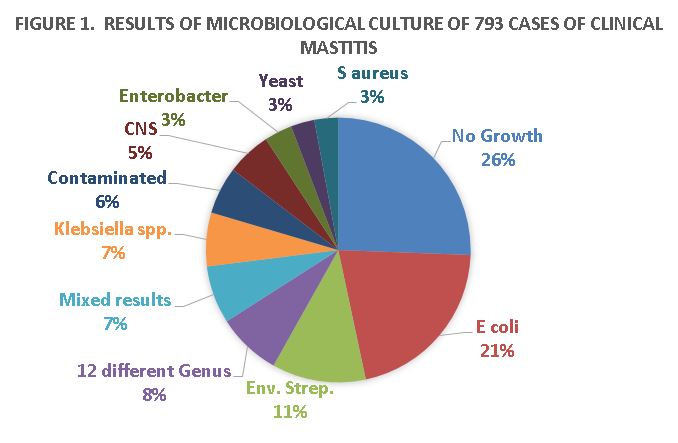

Post-milking teat dipping, dry cow therapy, well-maintained milking equipment, and culling of cows with chronic mastitis have successfully controlled contagious mastitis bacteria such as Streptococcus agalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus (Makovec and Ruegg, 2003). Milk samples collected from cows on Wisconsin dairy farms clearly demonstrated that environmental bacteria are the most common causes of clinical mastitis (Figure 1; Oliveira et al., 2013). Not all of these cases require antibiotic therapy. Some may respond to therapy, but cure rates for mastitis caused by pathogens such as yeasts, pseudomonas, mycoplasma, and prototheca are essentially zero. Thus, it is important to know the type of bacteria so that we can make better treatment choices.

What Should We Consider before Treating Mastitis?

Dairy farmers should work closely with their herd veterinarian to help develop treatment protocols, provide oversight for appropriate drug use, and monitor the success of treatment. More information about the role of veterinarians on dairy farms can be found at http://milkquality.wisc.edu/udder-health/antibiotic-drug-residue/

Intramammary antibiotic tubes are the most common treatment for mild and moderate cases of mastitis and are usually given without knowing the type of bacteria that is causing the infection (Hoe and Ruegg, 2006; Oliviera and Ruegg, 2014). Mastitis cases where the immune system has already cleared the bacteria from the cow (culture negative) often do not benefit from the use of antibiotics (Smith et al., 1985). However, bacteria-negative samples can occur when the cow remains infected but the number of bacteria that are shed is less than the detection limit of the laboratory. In some of these instances, antibiotic treatment may be beneficial.

In the United States, only two intramammary products (mastitis tubes) are labeled against E coli. Most mild and moderate E. coli mastitis cases spontaneously cure (without treatment), and it is difficult to justify across-the-board use of antibiotics for these cases (Suojala et al., 2010; Suojala et al., 2013). Additionally, there is usually no difference in cures in cows with E. coli mastitis between untreated and antibiotic-treated cows (Pyorala, 1988; Pyorala et al., 1994; Lago et al., 2011; Suojala et al., 2013). A New York study found a greater bacteriological cure for clinical mastitis caused by a variety of Gram-negative pathogens that were treated using intramammary ceftiofur (Spectramast LC™); however, treatment did not alter somatic cell count (SCC) or milk yield in the remainder of the lactation (Schukken et al., 2011). Thus, although treatment of Gram-negative (coliform) bacteria is not likely to be effective in most herds, there may be herds where treatment is beneficial. This is why it is important to keep good treatment records and follow treatment results like relapses of clinical cases.

In a Wisconsin study, 35% of the treatments were given to cases which were culture negative, and a further 17% were administered to cases for bacteria that had no approved antibiotic. Thus, half of the total cases that were treated were not likely to be effective and were difficult to justify (Oliveira and Ruegg, 2014).

What Types of Antibiotics Are Used for Mastitis Treatment?

In the United States, almost all approved intramammary antibiotics are labeled for treatment of Streptococci and Staphylococci, and there are no approved products for treatment of mastitis caused by Klebsiella or many other pathogens that cause clinical mastitis. Only two antimicrobial classes are represented among commercially available products that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Those classes are β-lactams (amoxicillin, ceftiofur, cephapirin, cloxicillin, hetacillin, and penicillin) and a lincosamide (pirlimycin). While several products have been withdrawn from the U.S. market, no new intramammary antibiotics for lactating cows have been approved since 2006.

In the United States, there are no antimicrobials that are labeled for systemic treatment of mastitis; however, extralabel use of some antibiotics (approved for dairy cattle for other diseases) is allowed under veterinary supervision. Systemic antibiotics to treat cows with severe mastitis are recommended as many of these cows are septicemic (bacteria in the blood) (Erskine et al., 2002). However, systemic use of drugs such as penicillin, ampicillin (Polyflex®), or ceftiofur (Excenel®, Naxcel®) will not reach therapeutic concentrations in the udder and their use is not recommended for mild or moderate clinical cases. As most mastitis treatments are administered simply based on observation of inflammation (without knowing the bacteria), most systemic treatments are difficult to justify both medically and to consumers.

What Is Labeled Antibiotic Use?

Various types of drug use are permitted on dairy farms. Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs (such as penicillin) may be used only under the exact label specifications and doses. A typical labeled use for OTC penicillin would be the treatment of bacterial pneumonia using a dose of 3,000 IU/lb (1 cc/100 lb) for no more than 4 days and by administration of no more than 10 cc in any one injection site. This dose would not be therapeutically effective for treatment of mastitis, and deviation from any of the labeled indications (such as treatment of mastitis, larger dosage , duration of treatment for more than 4 days, or administration of more than 10 cc in one site) is not considered OTC and must be done under supervision of a veterinarian.

Prescription products cannot be purchased without a veterinary prescription. This type of use requires that the product is used exactly as the label specifies. If the product is used outside of label specification, a veterinary label for extralabel use is required. The use of a commercially available flunixin product for treatment of acute bovine mastitis is an example of allowed prescription drug use. If administration follows the label directions (1 to 2 ml/100 lb via IV administration), then it is appropriate to follow specified label indications for milk and meat withholding. However, if the product is administered in the muscle or subcutaneously, the labeled meat and milk withholding periods are no longer sufficient, and the prescribing veterinarian must establish extralabel drug withholding periods.

Extralabel use refers to any use of a drug that is not specifically listed on the drug label and is only legal under the guidance of a local veterinarian who meets the criteria defined for a valid veterinary-client-patient relationship. The website of the Food Animal Residue Avoidance Database (FARAD) (http://www.farad.org/) is an excellent resource for information about guidelines for extralabel use. It is also important to know that not all drugs can be used in lactating dairy cows, even by veterinarians. A list of prohibited products can be found at the FARAD website.

One of the most confusing issues is the use of sulfonamides in dairy cows. No extralabel use of sulfonamides is allowed in adult dairy cows, and the label for sulfadimethoxine (the only labeled sulfonamide for dairy cattle) specifies that this drug may be used only for treatment of bovine respiratory disease, necrotic pododermatitis (footrot), and calf diphtheria. Thus, use of sulfonamides for treatment of other conditions (such as mastitis) is prohibited, even under veterinary supervision. Likewise, extralabel use of fluoroquinolones (Baytril® and A180®) is prohibited, and these compounds may not be used for treatment of bovine mastitis.

Guidelines for Responsible Antibiotic Use for Treatment of Mastitis

- Milkers should be trained to detect cases early and aseptically collect milk samples. These samples should be used to get a basic diagnosis (no growth, Gram positive or Gram negative) to guide therapy. Culturing with selective media can be done on-farm or in local veterinary clinics. Cows affected with mild or moderate cases of clinical mastitis should be isolated and milk discarded for 24 hours until culture results are known. If the farmer wishes to immediately initiate treatment, the treatment can be modified after culture results are known.

- Treatments should be administered only after a herd owner or manager, who works closely with the local veterinarian, has reviewed the medical history of the cow and evaluated the chances for therapeutic success. Cows that are third lactation or greater, have a history of previous clinical cases, or have a history of chronically elevated SCC are often poor candidates for routine therapy. Treatment decisions for these cows should be based on culture results and review of treatment outcomes from similar cases on each farm. In many instances, “watchful waiting” (isolating the cow and discarding the milk from the affected quarter) will be an appropriate therapy. In other instances, culling, drying off the affected quarter, or extended duration therapy may be preferred.

- Extended duration therapy is appropriate for some cases of mastitis but should be reserved for cases that will likely have improved outcomes. It is unlikely to be effective for treatment of cows that have multiple repeated cases of clinical mastitis.

- Except for rare cases, antibiotic treatment should not be administered to cows infected with pathogens that are unlikely to respond or for most non-severe cases that yielded no bacteria on negative. Watchful waiting is the appropriate strategy for these cases.

- The use of antibiotic treatment for mild cases of E. coli mastitis should be considered if review of the herd history suggests that a chronic strain is involved. In the absence of other data, a general rule is to initiate therapy if the cow has had increased SCC for at least 2 months or if the cow has other risk factors (first weeks of lactation, severe heat stress, very high production, etc.).

- Results of treatments should be monitored. The rate of recurrence (within 60 to 90 days) and SCC reduction (by 60 days) should be evaluated.

Summary

Clinical mastitis is detected from observation of inflammation (the cow immune response to infection). Many cases are negative for bacterial culture and will not benefit from antibiotic therapy. Other cases are caused by bacteria for which no available antibiotics are approved. Antibiotic treatments should be reserved for cases that will more likely benefit from therapy. Veterinarians should be involved in developing and implementing mastitis treatment protocols and should work with farm personnel and other professionals to actively monitor outcomes of treatments. Research evidence is available to help guide mastitis treatment decisions and to better select animals that will benefit from specific treatments.

Author Information

Pamela L. Ruegg, DVM, MPVM

University of Wisconsin,

Madison, Wisconsin, USA

References

- Erskine, R.J., P.C. Bartlett, J.L. VanLente et al. 2002. Efficacy of systemic ceftiofur as a therapy for severe clinical mastitis in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 85:2571.

- Hoe, F.G., and P.L. Ruegg. 2006. Opinions and practices of Wisconsin dairy producers about biosecurity and animal well-being. J. Dairy Sci. 89:2297-2308.

- Lago, A., S.M. Godden, R. Bey, P.L. Ruegg, and K. Leslie. 2011. The selective treatment of clinical mastitis based on on-farm culture results I: Effects on antibiotic use, milk withholding time, and short-term clinical and bacteriological outcomes. J. Dairy Sci. 84:4441-4456.

- Lago, A., S.M. Godden, R. Bey, P.L. Ruegg, and K. Leslie. 2011. The selective treatment of clinical mastitis based on on-farm culture results II: Effects on lactation performance including, clinical mastitis recurrence, somatic cell count, milk production, and cow survival. J. Dairy Sci. 94:4457-4467.

- Makovec, J.A., and P.L. Ruegg. 2003. Characteristics of milk samples submitted for microbiological examination in Wisconsin from 1994 to 2001. J. Dairy Sci. 86:3466-3472.

- Oliveira, L., C. Hulland, and P.L. Ruegg. 2013. Characterization of clinical mastitis occurring in cows on 50 large dairy herds in Wisconsin. J. Dairy Sci. 96:7538-7549.

- Oliveira, L., and P.L. Ruegg. 2014. Treatments of clinical mastitis occurring in cows on 51 large dairy herds in Wisconsin. J. Dairy Sci. 97:5426-5436.

- Oliver, S.P., B.E. Gillespie, S.J. Headrick, H. Moorehead, P. Lunn, H.H. Dowlen, D.L. Johnson, K.C. Lamar, S.T. Chester, and W.M. Moseley. 2004. Efficacy of extended Ceftiofur intramammary therapy for treatment of subclinical mastitis in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87:2393-2400.

- Pol, M., and P.L. Ruegg. 2007. Treatment practices and quantification of antimicrobial drug usage in conventional and organic dairy farms in Wisconsin. J. Dairy Sci. 90:249-261.

- Pyörälä, S., L. Kaartinen, H. Kack, and V. Rainio. 1994. Efficacy of two therapy regimens for treatment of experimentally induced Escherichia coli mastitis in cows. J. Dairy Sci. 77:333-341.

- Richert, R.M., K.M. Cicconi, M.J. Gamroth, Y.H. Schukken, K.E. Stiglbauer, and P.L. Ruegg. 2013. Management factors associated with veterinary usage by organic and conventional dairy farms. Journal American Veterinary Medical Association 42:1732-1743.

- Ruegg, P.L., and R.J. Erskine with D. Morin. 2014. Mammary Gland Health. Chapter 36 in Large Animal Veterinary Internal Medicine, Fifth Edition. B.P. Smith, editor. Elsevier. USA. Pp. 1015-1043.

- Saini, V., J.T. McClure, D. Leger, S. Dufour, A.G. Sheldon, D.T. Scholl, and H.W. Barkema. Antimicrobial use on Canadian dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 95:1209-1221.

- Schukken, Y.H., G.J. Bennett, M.J. Zurakowski, H.L. Sharkey, B.J. Rauch, M.J. Thomas, B. Ceglowski, R.L. Saltman, N. Belomestnykh, and R.N. Zadoks. 2011. Randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of a 5-day ceftiofur hydrochloride intramammary treatment on non-severe gram-negative clinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 94:6203-6215.

- Smith, K.L., D.A. Todhunter, and P.S. Schoenberger. 1985. Environmental mastitis: cause, prevalence, prevention. J. Dairy Sci. 68:1531-1553.

- Suojala, L. 2010. Bovine Mastitis Caused by Escherichia coli – Clinical, Bacteriological and Therapeutic Aspects. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Helsinki, Finland.

- Suojala, L., L. Kaartinen, and S. Pyorala. 2013. Treatment for bovine Escherichia coli mastitis – an evidence-based approach. Vet. Pharm. Ther. 36:521-531.