Introduction

Low-cost housing and feeding facilities can mean different things depending on the perspective you have. As an agricultural engineer, my perspective is typically system-based. The total system design is dependent on the management plan. The system cost includes the capital cost of the facility, supply costs, loss of animal performance, and the labor and management cost of operating the system. The owner invests in a system that will ultimately be profitable and fits within his or her own needs and farming philosophy.

It seems there is always a trade-off involved. In general, the lowest capital cost systems will have the highest annual costs. Capital is often spent to decrease annual cost. In an economic analysis, it is hoped that the partial budget shows the increased capital costs can provide annual savings to pay for the improvements over the life of the system. There may also be decreased labor costs and enhanced management ability.

I have tried to describe below several “low cost” concepts that have been employed to feed and house dairy cows. I focused on trying to minimize the capital cost of the systems. Although there is not time in this short discussion to provide a total system cost analysis, the information here could be used to determine the system costs for a particular situation including the capital and annual costs.

Please check this link first if you are interested in organic or specialty dairy production

Feeding Facilities

To minimize labor costs, today’s feeding systems are dependent on equipment access such as tractors, skid-steers, mixers, and feed wagons. The system design must allow easy access for equipment to move feed from storage to the cow.

Self-Feeding Systems

Self feeding of grain, silage, and hay is a labor-saving system adapted by farmers who do not have the capacity to move feed efficiently from storage to the cow feeding area. Feed is moved to the storage/feeding site during harvest. The system is designed to allow the cow access to the storage/feeding site.

Self-Feeding Hay

Large packages of baled hay (usually round bales) or wrapped baleage are stored in the feeding area. Individual bales or groups of bales are placed in a pattern that can be surrounded by temporary fencing. The temporary fence, which keeps cattle away, is removed from an individual bale or group of bales on a scheduled basis to allow access to the correct amount of feed for the required feeding period and to control waste. This is a common way to minimize the need for equipment in an outwintering situation.

Self-Feeding Silage

In this system, the silage pile, silo bag, or bunker face is sized to the number of cows in the group being fed. An electric wire or feed panel is used to control the amount of feed exposed to the cows. The cows eat off the silage face. The maximum height recommended is approximately 8 feet so that the silage face is not undermined. As cows consume the forage, the electric wire or feed barrier is moved (usually daily) to expose more of the face to the cows. The main concerns are accumulation of manure and mud around the cattle as they feed and possible feed waste as the forage drops to the ground. Placing the silage on an improved surface such as macadam or concrete allows easy cleaning of the accumulated manure and waste feed but also increases the total cost of the system. There is also the possibility of manure contaminating the feed, which may be a biosecurity issue.

Portable Feeding Systems

Portable feeding systems come in a variety of models and features. Movable bunks constructed from wood, steel, or plastic for feeding grain and silages can be skidded from one site to another within the feeding area. Feed is delivered by wagon to the bunk. Alternatively, the feeder can be placed on a running gear for easy transportation of the feed from storage to the feeding site. Hay feeders for small and large hay packages are also designed to be movable from site to site either by skidding or by trailering to minimize mudding problems associated with the manure accumulation and traffic around the feeding area.

Fence Line Feeding

Another low-cost system is an electric wire barrier in a pasture or lot separating cattle from the feed. Feed (usually grain) is laid just under the electric fence line to allow cattle access without trampling on feed. The main concern in this system is a potentially large amount of feed waste and muddy conditions on the cattle side due to increased cow traffic and manure accumulation in and around the feeding area. Moving the feed site periodically to rest it can reduce the muddy conditions but not totally eliminate them, depending on weather. Alternatively, the grain can also be placed in feed bunks or wagons along the fence line.

Drive-By Feeding Platform

To minimize muddy conditions and reduce feed waste, a feed barrier or fence can be developed with an improved surface for cattle, the feed platform, equipment access, or all three. Feed is delivered on one side of the barrier with no need to move equipment through the cow confinement area. The barrier can be a post-and-rail feed barrier or a line of self headlocks. The improved surface can be macadam or concrete. Figure 1 shows a feed barrier design used in freestall barns, feedlots, and barnyards.

The feed barrier can incorporate self-locking feed panels that are 8 to 10 feet long. The panels are sized with the correct size openings (from 5 to 8 openings) for different age animals. For dairy cows, the panels are sized to provide approximately 2 feet per cow. The use of self locks in the feed barrier is also a way to provide cattle treatment facilities and for herd health checks. This system allows easy feed bunk management by easily pushing up feed. Feeding can be done once a day and pushed up during the day. It is also easy to clean up waste feed by scraping it up with a tractor, skid-steer, or ATV with a blade. J bunks or H bunks can be used to eliminate the need to push up feed, but they are harder to clean out.

Housing Facilities

The housing system should accommodate the need for cows to have shade in the summer, wind protection in the winter, and a clean, dry hair coat. Cold temperatures can be managed with nutritional changes and protection from the wind along with a dry bedded resting area. Hot temperatures can cause heat stress, realized in reduced milk production and reproduction problems. Cows should have access to natural or artificial shade during the hottest part of the day and easy access to water at all times. The worst time for cows is cold, wet weather typical of fall and spring. Muddy conditions usually result, and the hair coat is constantly wet, causing stress on the cows and high somatic cell counts.

Wind Breaks

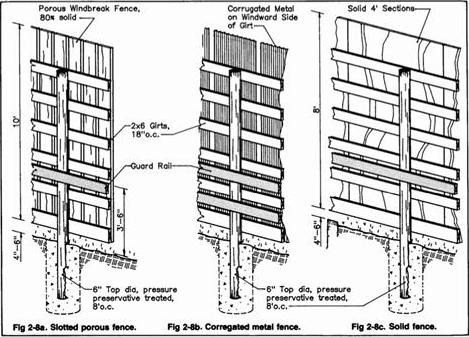

Natural tree lines and wooded areas can act as windbreaks to protect cows. Temporary windbreaks can be constructed from large square or round bale packages of hay or bedding or forage boxes. The windbreak height of 8 to 10 feet can be accomplished with a stack of two to three bales high. The bales are also stacked side by side to provide a solid windbreak barrier. A windbreak fence can also be constructed from wood posts and boards or synthetic cloth as shown in Figure 2.

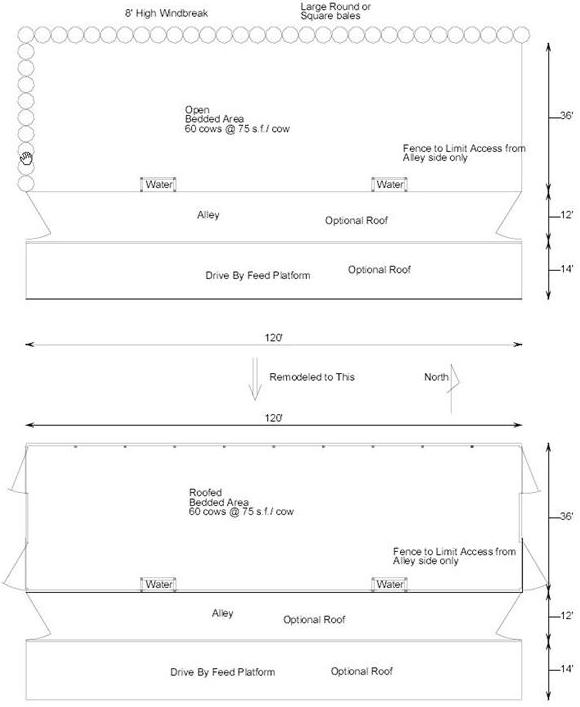

Figure 3 shows a design for a bedded area sized for 60 cows with a windbreak on the north and west sides. A drive-by feeding system is used to feed cows on the south side. A windbreak could also be added to the east side if wind patterns at the site require it.

Bedded Pack Housing

Loose housing allows the cow free access between the resting, feeding, and water spaces. There is some advantage to separate these spaces one from another to control manure deposition in specific areas to help maintain cleaner cows. Where there is feed and water, there is more manure accumulation compared to the resting space. Where there is water, there is also the possibility of mud. So it is beneficial to have improved surfaces at least around the feed and water areas. The bedded area does not require concrete since it provides the soft, comfortable resting surface, although it does make cleaning out the accumulated manure pack a little easier. Consider the site carefully since ground water could be contaminated as seepage moves down into the soil under the pack

Bedded Resting Space Needs

The bedded resting space should provide between 50 to 100 square feet per cow depending on cow weight. A lying Holstein cow occupies approximately 25 square feet and needs almost twice that amount of space for lying down or rising. Information on other configurations includes:

- 50 square feet per cow is minimal and will require larger amounts of bedding rates to keep cows clean. It also will increase the total height of the accumulated manure and bedding pack over time, which can possibly restrict access to the pack as manure and bedding accumulates.

- 100 square feet per cow may be excessive, requiring more building space that increases capital cost.

- 75 square feet per Holstein cow and 60 square feet per Jersey cow seem to be common values for well-managed systems. It provides enough space for the cow to rest and move among other cows without causing injuries to other lying cows.

The bedded area should be rectangular with a maximum depth or width of 36 feet from the feeding alley to the back of the bedded area (Figure 3). Cows tend to lie around the perimeter of the bedded space. The bedded surface can also be sloped downhill from the rear to the front of the space which will tend to make the cows all lie in the same orientation.

Additional space for feeding and water access must also be included in the overall system design. To manage cow cleanliness, either the group size can be adjusted or the quantity of bedding used per day can be adjusted.

Bedding Amounts and Frequency

As the bedded area per cow decreases, the amount of bedding required to keep the cows clean increases. Depending on cow weight, 15 to 25 pounds of bedding per day per cow should be added to the pen every day to maintain clean cows. Wood shavings, clean straw, corn fodder, and waste grass hay are common bedding choices. Waste hay should be chopped before adding to ease cleaning the pack. Depending on the cost of bedding, this can cost $0.25 to $0.50 per cow per day. The bedded pack is commonly used during the winter housing period between December 1st through the end of March, or approximately four months. In this situation, the bedded pack acts as a manure storage system. It is common to clean out the pack at the end of the winter housing season or at three- to four-month intervals if used continuously.

Several other management decisions can help maintain clean cows. For small herds (30 to 40 cows), policing the bedded area daily by removing manure patties can help maintain cleaner cows and minimize the amount of bedding required to maintain clean cows. Some experiential data suggest the amount of bedding needed to keep cows clean can be reduced by 50% by policing the area. Daily removal of accumulated manure from adjacent alleys near feed and water areas can also help maintain cleaner cows. It is helpful to have an area designed to collect the scraped manure temporarily.

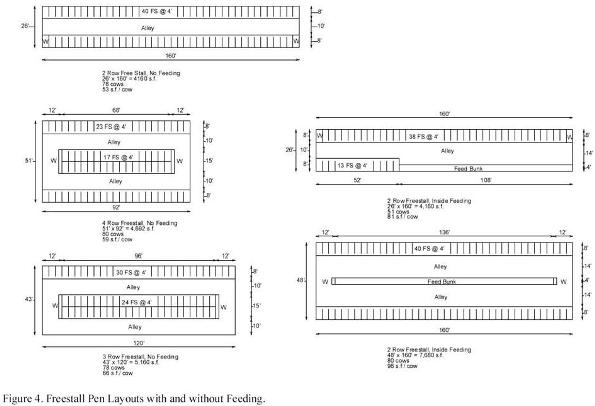

Freestall Housing with Outside Feeding

Figure 4 shows several different arrangements for housing and/or feeding cows in freestall barns with outside or inside feeding. These arrangements minimize the capital cost by covering the least amount of resting and/or feeding area as possible. The arrangements are shown for herd sizes ranging from 50 to 80 cows and are shown from the least amount of building area used per cow (53 s.f./cow) through the most building area used (96 s.f./cow). In the first three cases, the feeding area is placed near the housing area but is not roofed, although that is an option. Often there is a barnyard or concrete area adjacent to the building that can be remodeled into a drive-by feeding system for the cows.

In the last two cases, the common alley between the resting area and the feeding area is roofed as well, which increases the building area required per cow. In these two cases, the feeding equipment must be driven through a manure alley, which requires that the cows be removed from the area during feeding. This situation may also be a biosecurity risk by contaminating feed with tracked manure.

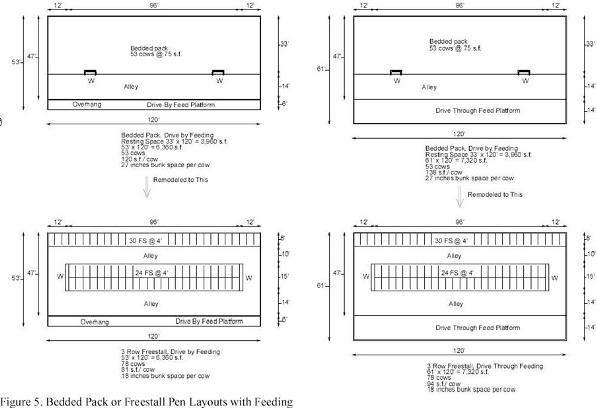

Bedded Pack and Freestall Barns with Inside Feeding

Figure 5 shows two bedded pack barn arrangements in a building width that can eventually be remodeled into a freestall barn with the addition of concrete alleys, freestall platforms, and waterers. In either the bedded pack or freestall pen layout, a concrete alley is placed between the feed platform and the resting area. The waterer for the bedded pack arrangement is placed adjacent to the bedded resting space and should have a barrier to prevent cows from accessing the waterer from the bedded pack area to reduce wet bedding and excessive manure accumulation in the bedding around the watering site. Cows should only access the waterer from the alley adjacent to the feed bunk.

In either layout, the alleys are usually scraped daily. The bedded space can have a macadam base to save costs and is sized for the correct number of cows which also matches the feeding space needed for the group. The options for roofing over the area include roofing over the bedded pack (33 feet wide), roofing over the bedded area and the cow alleys (47 feet wide), or roofing over the entire housing and feeding area (61 feet wide). Although the area per cow is increased with these options, the ability to manage feeding is improved. Roofing the cow resting and walking areas can also eliminate the need to handle the contaminated manure from rainfall runoff events from unroofed cow confinement areas.

Click here for a printable version of Figures 4 and 5 (PDF).

As can be seen in Figure 5, the freestall arrangement uses less space per cow compared to a bedded pack system. That does not necessarily mean the cost is lower for a freestall barn, but the cost comparison between bedded pack and freestall arrangements for the same building space should be looked at carefully to make a fair comparison for the total system cost. In these cases, there is approximately a 40 s.f./cow difference in space needs between the freestall barn and the bedded pack barn.

Remodeling Buildings for Cow Housing

To reduce the capital costs for cow housing, some post frame buildings such as machine sheds or loafing sheds can be remodeled into bedded pack or freestall pen arrangements. The typical width of a bedded resting area can range from 18 to 36 feet. Additional space will be needed for alleys and feeding. Table 1 shows the minimum and recommended building width needed to accommodate different freestall barn row arrangements but also allow the space to be operated as a bedded pack system.

| Building Width | Freestall Barn Number of Rows and Feeding Location | |||||||

| 1 row | 2 row no inside feeding | 2 row drive-by outside feeding | 2 row drive-by inside feeding | 3 row drive-by outside feeding | 3 row drive-by inside feeding | 4 row drive-thru feeding | 6 row drive-thru feeding | |

| Minimum Width, ft. | 19 | 24 | 35 | 49 | 43 | 57 | 88 | 104 |

| Recommended Width, ft. | 22 | 25 | 38 | 52 | 48 | 62 | 94 | 114 |

Summary

Achieving a low-cost housing system for cows is not as simple a decision as it might seem. All the costs, including the total, capital, and annual costs, must be considered in the decision. It also depends on how an individual producer chooses to protect the cows in the resting and feeding areas and how much building roof is necessary to meet their goals. Both systems have advantages and disadvantages, and these should be considered in the decision process for an individual farm.

References

- Beef Housing and Equipment Handbook. MWPS-6. MWPS, Ames, IA 50011.

- Penn State Dairy Housing Plans. NRAES-85 NRAES 152 Riley Robb Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853.

- Housing and Manure Management CD. CDP. UW Cals-UWEX 608 265-3030.

Author Information

David W. Kammel

University of Wisconsin-Madison

460 Henry Mall

Madison, WI 53706

608-262-9776

dwkammel@wisc.edu</center>