Contents |

Introduction

Discovering the “value” of milk in the market place has always been troublesome. Prior to about 1916 milk dealers were better informed about market conditions than dairy producers. Plants formed trade associations such as the New York Milk Exchange, and published monthly prices to their member plants that would be charged for milk. From about 1916 through 1933, collective bargaining agencies for dairy producers formed to negotiate milk prices with the milk dealers trade associations and began to publish a monthly price list of their own that would be charged for milk sold. With the passage of the 1933 Agricultural Agreement Act, Marketing Agreements formed the basis for compliance of contracts between producer groups and milk dealers. A 1935 amendment to the 1933 Act authorized the creation of Federal Milk Marketing Orders.

Federal Milk Marketing Orders have been the dominant tool used to set minimum prices paid for milk since 1935. Individual federal orders may have unique regulations, but several concepts are basic. Federal orders can only compel fluid milk plants to participate in an order. It is a privilege for all other plants to participate allowing them access to additional funds to pay producers for milk purchased. Acting as something like the transaction police, federal orders determine a minimum price paid for milk according to the products produced, they audit plants to assure compliance with order regulations, they “pool” or distribute the funds to plants so that all plants can pay producers a minimum “blend” or “statistically uniform” price irregardless of the products their milk was used to produce.

Please check this link first if you are interested in organic or specialty dairy production

Determining a minimum price in the market place is tricky. If milk prices are set much lower than market-clearing levels then there is little benefit to having an order determining minimum prices. However, a much bigger problem exists if minimum prices are higher than market-clearing levels. In this case, milk producers will want to sell more milk than consumers are willing to buy. The only relief under this scenario is that dairy cooperatives are allowed to sell distressed milk at lower-than-minimum prices. But, under these conditions, producers would soon leave cooperatives.

A minimum price that would entice milk producers to sell somewhat less than consumers want to buy is fairly easily remedied by bargaining with plants to pay somewhat more than the minimum price. These so-called “over order premiums” exist in varying levels in most all federal orders today.

There have been a variety of methods used to price milk over the years. 40 years ago, in 1967, USDA’s Summary of Major Provisions in Federal Milk Marketing Orders lists 7 methods being used singly or in combination in 73 different orders at that time. The Minnesota-Wisconsin (M-W) price series was the most common method for pricing manufacturing milk in 1967, but also in play were:

- Butter-powder price formula

- The lower of the M-W or the Butter-powder price formula

- A 3-product price (survey of plants purchasing milk)

- The M-W + 15¢

- The higher of a Midwest condensery average minus 20¢ (the average of prices paid for milk by 6 specific plants), a local plant average minus 20¢, or the butter-powder price formula minus 20¢

Today, the question remains, “What is the value of milk?”

I will posit that there are basically six different strategies, with a multitude of variations, that might be employed to determine a value for milk. Those include:

- Product price formulas

- Economic formulas

- Survey of unregulated milk

- Only pool differentials—don’t worry about the value of manufactured milk

- Futures markets

- Spot auctions for milk

Product Price Formulas

Product price formulas have been in use for decades and are currently being used to determine milk component values in federal orders. They utilize a fairly simple technique that looks at the value of the products made from milk and back-calculate into an implied value for the milk used. There are three basic values in these formulas: product prices, make allowances, and yield factors. All three basic values become contentious issues in determining the value of milk.

Product Price Series

The question of product prices becomes one of which products and which price series to use. We are currently using a National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) survey of transactions for cheddar cheese–40 lb blocks and 500 lb barrels, dry whey, butter, and nonfat dry milk powder.

Although we are currently using the NASS survey of product prices many folks have suggested using the Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s (CME) spot prices for cheddar cheese as a replacement benchmark for cheese values and possibly butter and nonfat dry milk as well. The appeal to such a change is not in an intrinsically better benchmark (current NASS nonfat dry milk prices notwithstanding)—indeed detractors of using the CME suggest that such little volume is actually traded on the CME that the market may be too “thin”. This argument seems fallacious as most commodity cheeses are contract priced from the CME benchmark.

A simple regression to explain the NASS cheese price based only on the CME cheese price shows that more than 87 percent of the variation in the NASS price can be explained by the CME price alone. However, it takes a little time for the CME price to be known and implemented into contract price movers, for NASS to collect those contract prices and for NASS to summarize and report those prices. If we simply lag the CME price by one week almost 96 percent of variation is explained and the optimal lag is two weeks where nearly 99 percent of variation is explained. In other words, the CME price will move the market as well as the NASS price series will—it’s only a matter of timing.

Many folks have noted that the advantage of using the CME is in fact the timing. You could shorten the lag between advanced pricing of class I and class III by two weeks and lessen the possibility of having unusually large producer price differentials (PPD) during times of rapidly falling prices or even more disruptive negative PPDs and depooling when prices are rapidly rising.

Yield Factors

Since federal order reform in the year 2000, yield factors have seldom been discussed. Yield is important to determine if you are trying to back-calculate into a milk value from products produced. For example, if cheddar cheese is selling for $1.30 per pound and we can make 10 pounds of cheese from 100 pounds of milk, then the yield factor is 10 and (absent a make allowance and other complications) the milk should be worth $1.30 * 10 = $13.00 per cwt. If we can only make 9.5 pounds of cheese from the milk then the milk is only worth $1.30 * 9.5 = $12.35 which is quite a bit less.

We wouldn’t expect yield factors to change much over time. But, technological advances may allow us to capture more milk solids in the cheese suggesting that yield factors be adjusted occasionally. At the very least, yield factors should be evaluated from audited data over time to see if the original assumptions are still accurate.

Make Allowances

In the same way that yield factors are important to product price formulas, make allow-ances are also important and much more likely to change over time. Make allowances account for the fact that it cost you something to turn 100 pounds of milk into dairy products. Using the simple cheese example, a plant couldn’t really afford to pay $13.00 for milk if they were selling their cheese for $1.30 because the labor, utilities, packaging, etc. couldn’t be recovered from the sale of the product. So, a make allowance is subtracted from the formulas. For example, it if cost plants 20 cents to make a pound of cheese, then the simple product price formula might look like ($1.30 – $0.20) * 10 = $11.00 and not $13.00.

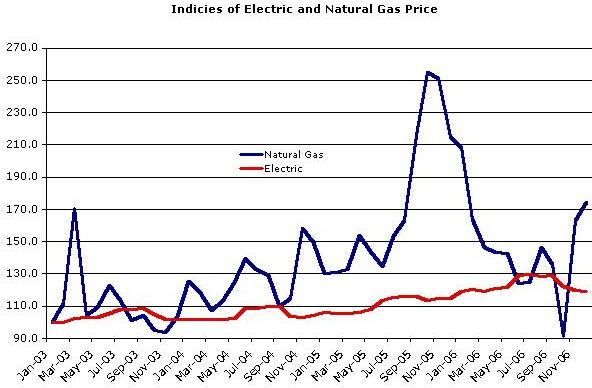

Costs of processing in plants will vary over time. Unit costs (prices) for many items like labor would only be expected to increase over time. However, plants have replaced a good deal of their labor costs with automation and capital purchases so it isn’t easy to surmise what has happened to labor costs per pound of cheese over the last 10 years. Some prices, like energy have had both dramatic increases and declines over the past few years and make allowances need to adapt to the realities of these changes in costs. In unregulated industries, a processor would pass the cost increases along to retailers and consumers who would make new purchase decisions. But, in this regulated industry, an increase in the sales price without a concomitant change in the make allowance only results in an equal change in the input price for milk purchased.

Processing costs will change, sometimes rapidly, and a mechanism for changing the make allowances should be found that is less cumbersome and contentious than the federal order hearing process.

Pricing Components

Multiple component pricing (MCP) has been around for many years. If you include pricing butterfat and skim milk as component pricing, then MCP has been around since Babcock invented an accurate and inexpensive test for butterfat in milk in 1890.

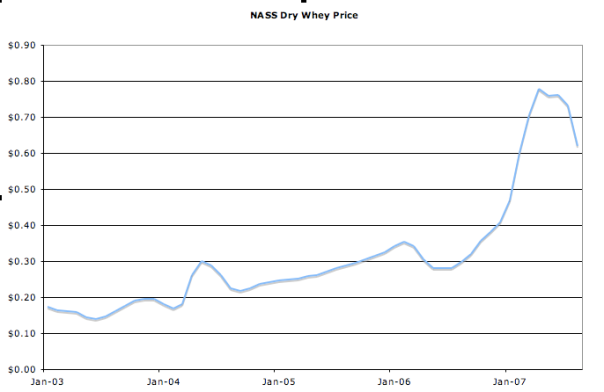

In the same way that imagining which products should be included in a product price formula, we can wonder which components in milk should be priced. Currently in MPC orders we are pricing butterfat, true protein, other solids and water (through the PPD)1. Butterfat is relatively straight-forward and is priced from NASS butter prices. Protein is more complicated in that we begin with cheese prices and subtract the butterfat value from the cheese price to impute a value for protein. The other solids value is meant to reflect the value of lactose, minerals and ash in milk and has been calculated from dry whey prices.

Recently, dry whey prices, which had varied between 15-30 cents per pound have sky-rocketed to more than 70 cents. Dry whey is the dried solids left over from the cheese-making process. The bulk of these solids are lactose with some minerals like calcium. However, a substantial portion of the composition of whey is the serum protein sometimes called milk albumin. This is very digestible and high-quality protein with a value in its own right. Most of the value currently placed on dry whey is a result of the protein. The whey protein has been so sought after that more purified protein powders including whey protein concentrates and isolates have increasingly been manufactured.

If we are pricing proteins to dairy producers, perhaps we should add the value of the protein in whey to the protein calculation from cheese. This would send dairy producers a better market signal regarding the value of true protein versus other solids.

This calculation is no more complicated than the current protein formula where the butterfat value is subtracted from the cheese price. The other solids value could be valued at a lactose price and the dry whey price partitioned into a protein value, which can be added to the casein protein value already determined from the cheese price and a lactose value. If desired, the lactose value could be subtracted from the nonfat dry milk or skim milk powder price to provide a protein value in class IV.

Some folks have also wondered about using butter and nonfat dry milk in the class IV formulas but leaving out buttermilk powder as the other product produced from milk in these plants. One caution in pricing all of these products in our formulas is that we may be “cutting too close to the bone”. In other words, we could be in danger of creating a minimum price that is above market clearing levels under some product price scenarios.

Economic Formulas

Economic formulas have been used at different points of time in the dairy industry. Perhaps the most notable example is the support price that was “snubbed” between 75-90 percent of parity. The index point for parity was determined from a period when it was thought that farm prices were well aligned with non-farm prices (1910-1914). The support value of milk was updated within this range with a market basket of input prices for farms. Of course, in the early years of price support, the price of a mule was an important input cost to farmers but became obsolete over time. This points out one type of problem with economic formulas—they must be regularly updated.

Another type of economic formula that is often espoused by farm groups is cost of production. The notion here is that it makes sense to at least pay for milk the cost of producing it. The Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act, which authorized federal milk marketing orders, declares that orders should take into account the cost of producing milk when determining milk prices. The complication of using cost of production as the primary approach to pricing is when one considers whose cost of production will be used—are you going to try to cover the highest cost producers to assure profitability to all farms, or the average farm, or the lowest cost producers and let premiums fill in the gap.

We also see in annual farm financial summaries that the cost of producing milk varies in lock-step with the price of milk. As milk prices rise, dairy farmers have the incentive and the wherewithal to purchase additional inputs to produce more milk. So, costs of production increase. As milk prices decline, so do the costs of producing milk as farmers put off longer-term expenses such as painting the barn or new equipment purchases. Under cost of production pricing, if a natural disaster occurs (drought, excessive rain, etc.), the costs of producing milk will have increased and the regulated milk price with it. But, once the regulated price has increased, producers will continue to spend the additional profits to produce more milk even when the natural disaster has past and the cost of production does not drop.

This points out a second problem with economic formulas that only take into account one side of a market place—either supply or demand. Cost of production proposals, which are only supply side, will have the effect of ratcheting the price upwards along the long-run supply curve. Although we have never had one proposed, demand side economic formulas would be expected to have the effect of only moving the price down along a demand curve.

Another kind of economic formula that has occasionally been proposed relies on statistical estimation. For example, we could look take the class III price and try to explain its variation relative to labor costs, energy costs, feed costs, gross national product, price of dairy substitutes like soy or chicken, etc. If we could construct an econometric model with satisfactory explanatory power, then it could be used to determine a market value for milk. One problem of using this type of economic formula is that it will need to be re-estimated occasionally to account for shifts in the underlying factors. Another problem is that it is difficult for lay people to understand—in other words, it isn’t transparent and thus subject to criticism when the price moves in a direction that producers, processors or consumers don’t like.

Survey of Unregulated Milk

Economists are big fans of the marketplace when it comes to sorting out prices. The Minnesota-Wisconsin (M-W) price series was based on a survey of unregulated, grade B milk purchased by manufacturing plants. This worked well for nearly 40 years but was abandoned because of dwindling grade B milk production in the region. The success of a survey approach is to survey unregulated markets where prices are moving up and down based on supply and demand conditions. When the grade B supply became too small, the next-best option was to move up the market chain one step to survey unregulated buying and selling of wholesale products made from milk and try to infer a value of milk from those product prices. Hence, our current product price formulas.

One idea that has been discussed is to create an area of unregulated milk sales and observe the prices being moved by the marketplace. As mentioned earlier, federal orders are all about class I markets and I think that we often lose that perspective. Other classes of milk may be associated with class I markets to have access to a portion of the class I dollars. The cost of being associated with the market is that these pooled plants must “perform” for the class I market by being willing to give up some of their milk to the class I plants if it is needed. Many orders have requirements that a certain percentage of a manufacturing plant’s milk be delivered to a class I plant during certain months of the year to demonstrate their willingness to supply the class I market. The milk may not be used by the class I plant, but it could be.

The Upper Midwest has the lowest class I utilization in the federal order system. It might be the case that plants associated with that order continue to have access to the class I market and continue to receive a pool draw of class I dollars provided that they “perform” for that market. Associated plants would be subject to audit and other regulations, but would otherwise have unregulated prices. They would be allowed to negotiate a manufactured milk price that would “clear the market”. This price would be surveyed like the old M-W and administered as the basic formula price in other federal orders.

One problem with this approach is that manufacturing plants in the Upper Midwest are determining their milk price at the same time that the milk is being used in their plants. Plants outside the region will have those prices administered more than a month later (it takes time to collect and summarize the survey data). When prices are moving up, Upper Midwest plants are at a price disadvantage in the marketplace for their products and the opposite is true when prices are moving down. This would be an obvious issue to be contended.

Only Pool Differentials

The previous suggestion of creating an unregulated supply of manufacturing milk could be expanded to all federal orders. This would side-step the problem of out-of-sync milk prices. Only pooling differentials has been suggested before but dismissed as unworkable when you wouldn’t know which plants should be associated with the various pools. By having the same performance requirements as is in place today, it would be no easier than it currently is to associate distant milk with a particular class I pool.

Performance requirements are not the only regulatory burden for plants. Reporting and auditing would still have to be performed as a necessary step to calculate the pool draw in any given month. But, under this scenario, it wouldn’t be necessary to announce anything like a basic formula price or class mover. All plants, even class I plants, would have to negotiate the price of milk from producers or their organizations. However, all plants associated with the pool (even class I plants if the full value of the differential was pooled) would have a pool draw that would allow them to pay more than would otherwise be the case. Of course, class I plants might only make an equalization payment into the pool and not be eligible for a draw.

A couple of problems with this approach arise. One is that USDA may not believe that they have authority under the ’35 act to do this. The problem is that they cannot assure that all producers would be treated equitably. In other words, they couldn’t guarantee the same minimum prices to producers in the same zip code selling milk of equal component composition. Another problem is that the current success of futures markets for class III milk rests on a cash-settled contract. If the USDA, as the neutral third party, did not announce a class III price, there wouldn’t be a cash settled market. Previous experiments with delivery contracts for milk were not successful.

Futures Markets

Futures markets have been suggested as method of price discovery for milk. Indeed, price discovery is what futures markets are all about. They distill information that might impact milk production and demand for dairy products and they move toward a consensus value for milk produced and sold at a future date. Futures values for any product should converge toward the cash market price as the end of a contract draws near.

A mechanism for using futures markets as the means of regulating prices has been suggested as calculating the contract-volume weighted average price for milk in the last month that a contract is traded—perhaps dropping the last day or two of trading to allay concerns about being squeezed in a delivery contract. Obviously, using the futures markets to determine the regulated minimum price means that you cannot use the USDA’s price announcement for a cash-settled contract. And, as noted above, a delivery contract for a bulky and perishable product like milk at a single destination has its own set of problems.

Spot Auctions for Milk

Cash markets for cheese and other dairy products have existed for years. The Greenbay Cheese Exchange was established in 1918 and operated until 1997 at which time its function was replaced with spot market sales at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Even the Greenbay Cheese Exchange was pre-dated by the New York Cheese Exchange begun in 1871. The purpose of these spot markets is little different today than in years past. They provide an alternative market or clearinghouse for the sale or purchase of product that is not being sold under contract. Transactions on the Exchange, or even unfilled offers and bids, can move the posted price up or down.

Exchanges operate under well established trading rules. The product is well defined; i.e. you know what you are buying or selling in advance in terms of quality and quantity. Delivery will take place at a pre-determined location. And importantly, trading takes place publicly where activity can be observed. Although the sales volume that is typically sold through the exchange represents a small proportion of national volume, it serves as a market beacon as to the value of product at any point in time. The majority of cheese—at least commodity cheese—in the U.S. is contract priced off of the price movements on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Buyers or sellers who observe prices that they don’t believe are warranted can challenge the price by buying or selling on the Exchange themselves.

For the same reasons that delivery-based futures market contracts are problematic—the product is bulky and perishable to deliver to a distant location—a national spot market for milk would be challenging if not unworkable. However, technology may make such an idea possible. Just as eBay has revolutionized person-to-person transactions for all kinds of products, online auctions might work for milk. Any buyer or seller could post a load of milk F.O.B. the buyer’s or seller’s location. Nearby plants or seller’s could bid on the load and when a transaction takes place, the value of milk at that location on that day is established. The bids and successful transactions could be observable by anyone. A monthly price could be established and announced from a weighted average sale of product from around the country. Location corrected values could also be established if desired.

Problems with technology-assisted spot auctions for milk might include sales between plants for the purpose of moving market prices lower or sales from a cooperative to a cooperatively owned plant to move prices higher. These problems could probably be overcome.

Summary

Discovering a value for most products has never been easy but seems to be particularly difficult for milk. Non-perishable products have the advantage of storability. If you don’t like the price, a buyer’s willingness to pay can be challenged by withholding product for a period of time. With most products, a demand curve can be examined by speeding up or slowing down production—something that is also difficult in the short-run with milk. It has also been true that there are many fewer buyers of milk than sellers and these characteristics, among others, have traditionally been thought to put dairy farmers at a disadvantage in the marketplace. This disadvantage has been neutralized by regulation in many countries of the world including the United States.

Many industry participants have petitioned for less regulation citing that conditions are different today than they were 100 years ago. However, with or without regulation, a value for milk would have to be determined. I have presented six basic options for consideration which include:

- Product price formulas and some modifications from current implementation

- Economic formulas

- Survey of unregulated milk

- Only pool differentials—don’t worry about the value of manufactured milk

- Futures markets

- Spot auctions for milk

Of these options, I would rank product price formulas as the most workable solution for regulated prices at this time—although I may be influenced by preferring the devil I know. I also think that creating an unregulated region to survey is unworkable as are economic formulas and using futures markets. If the authorizing act were changed, then only pooling differentials could work in a regulated world. And finally, I can imagine that spot auctions for milk could be made to work in either a regulated or unregulated framework. The market will need some mechanism to discover a value for milk.

1This represents what producers are paid in federal orders with MPC pricing. Class III plants will pay for butterfat, protein and other solids while other classes will pay for butterfat and skim or nonfat solids.

Author

Mark Stephenson

Cornell Program on Dairy Markets & Policy